An Energy-Based Perspective on Microbial Food Web Structure

The oceans are teeming with microbes like bacteria and phytoplankton that play an outsized role in climate regulation. These microorganisms absorb carbon, cycle nutrients, and form the base of the ocean food web. Yet despite their importance, scientists know relatively little about them: what they eat, how fast they grow, or how they interact with predators and each other.

With millions of microbes packed into as little as a single milliliter of ocean water, building models that can accurately capture microbial food webs, and predict how they might shift in response to global climate change, has long been a daunting challenge. But now, researchers at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) have developed a new computational model to tackle this problem.

Built on a principle from thermodynamics, the branch of physics that studies how energy moves within a system, the model lets researchers explore how microbial food web structure changes over short and longtime scales. Their findings, published Dec. 19 in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface, show that microbial communities self-organize to dissipate energy more effectively over time, rather than burning through it instantaneously.

“Traditional models of microbial food webs are often brittle,” said MBL Senior Scientist Joseph Vallino, senior author on the study. “They fit the data we have, but when you try to extrapolate beyond that, their predictions fall apart.”

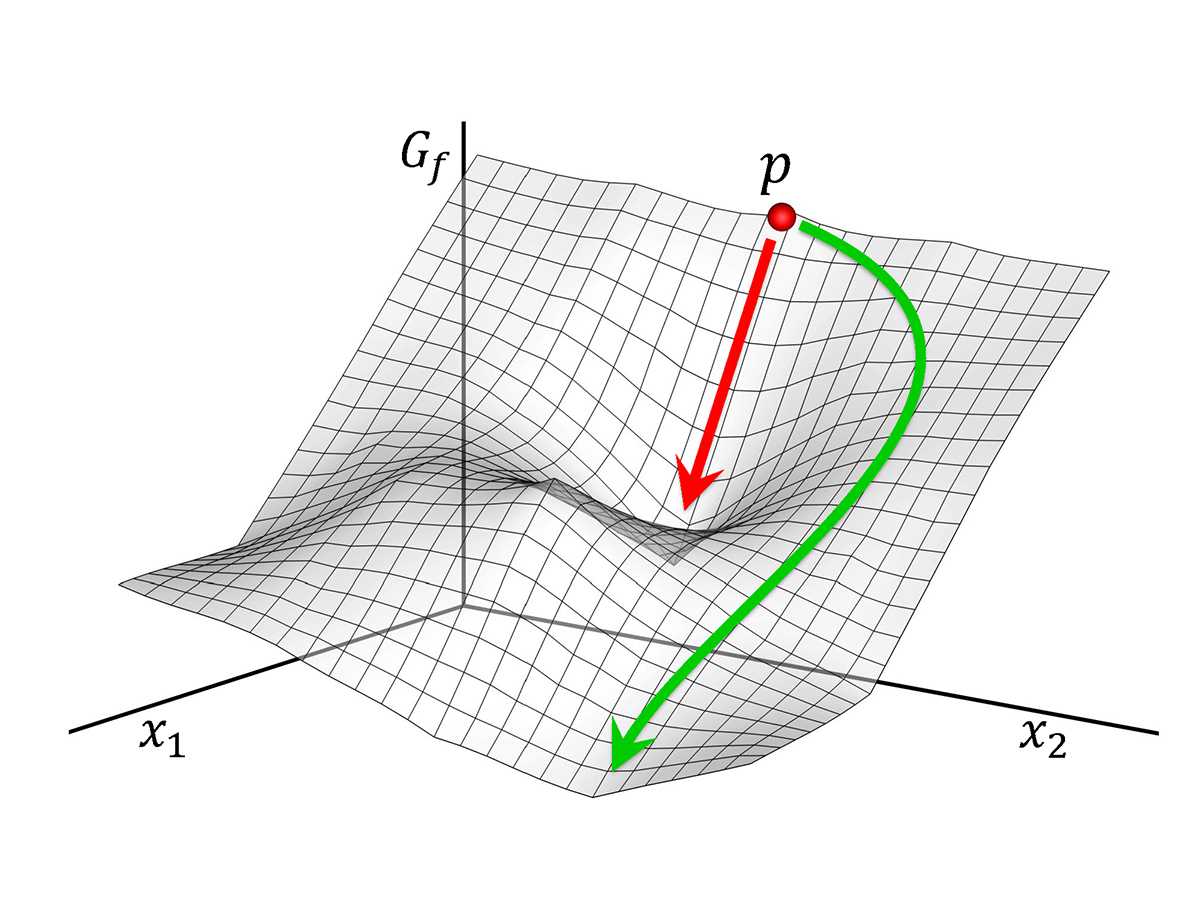

When Vallino learned about a principle from thermodynamics called maximum entropy production (MEP), which suggests that systems, living or non-living, tend to organize in ways that maximize the dissipation of energy, he realized it could offer a new way of understanding microbial communities.

In non-living systems, this principle is easy to spot. Hurricanes, for example, form to quickly move heat from the warm ocean to the cooler atmosphere, pushing the system toward balanced temperature. But if living systems did the same, Vallino explained, they would burn themselves out.

To capture this distinction, Vallino and his collaborators Julie Huber, Senior Scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and MBL Postdoctoral Scientist Olivia Ahern have built a computational model that doesn’t assume who eats whom or how microbes behave. Instead, it lets the food web self-organize according to a single guiding principle: maximize energy dissipation over a set period of time.

When the team ran the model over a short timescale of one to two days, the emerging food web was dominated by fast-growing “specialists” that quickly consumed the most energy rich resources, leaving others unused. But when the model optimized energy dissipation over longer periods of days to weeks, a more diverse microbial community emerged, with some specialists alongside slower-growing “generalists” able to use a wider range of resources.

These differences, Vallino explained, capture the timescales that life has evolved to operate on. Microbes can anticipate predictable changes in their environment, like phytoplankton ramping up photosynthesis each morning, or allocating resources to survive periods of scarcity.

The team is now testing the model’s predictions in the lab using carbon-13 labeling, a technique that “tags” carbon atoms so scientists can track which microbes consume which nutrients and how that energy moves through the food web.

By comparing the model’s predictions with experimental data, they can refine its ability to forecast how microbial food webs—and, in turn, marine biology and chemistry—will respond to global climate change.

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation, and the Simons Foundation under The Simons Collaboration on Computational Biogeochemical Modeling of Marine Ecosystems (CBIOMES).

Citation:

Joseph John Vallino, Olivia Ahern, and Julie A. Huber (2025) Deriving microbial food web structure by maximizing entropy production over variable timescales. Interface Focus. DOI: 10.1098/rsfs.2025.0023

—###—

The Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) is dedicated to scientific discovery – exploring fundamental biology, understanding marine biodiversity and the environment, and informing the human condition through research and education. Founded in Woods Hole, Massachusetts in 1888, the MBL is a private, nonprofit institution and an affiliate of the University of Chicago.