Jellyfish: A Model for Wound Healing

Jocelyn Malamy of the University of Chicago makes jelly donuts—and not the edible kind. In the MBL Whitman Center this summer, Malamy is removing the centers of her jellyfish specimens to observe how they regenerate.

“One of the few animals that rival the ability of plants to regenerate are those in the cnidarian phylum, like jellyfish,” says Malamy, who also studies root and shoot formation in plants.

Her cnidarian of interest, Clytia hemispherica, is a transparent hydromedusa that grows about a centimeter in diameter. Clytia has an umbrella-like (bell) structure girdled by tentacles. The bell is enclosed by two monolayers of ectodermal epithelial tissue that sandwich the gut and non-cellular jelly. The tubular mouth, called the manubrium, hangs down from inside the bell like an umbrella handle.

“Clytia is an attractive system not only because it’s good at wound healing and regeneration,” she explains, “but also because it has a rapid reproductive cycle, simple genetics, and is easy to maintain in large numbers.” The Clytia research community is designing tools to manipulate the genome, allowing scientists to gain a deeper understanding of which genes regulate which processes.

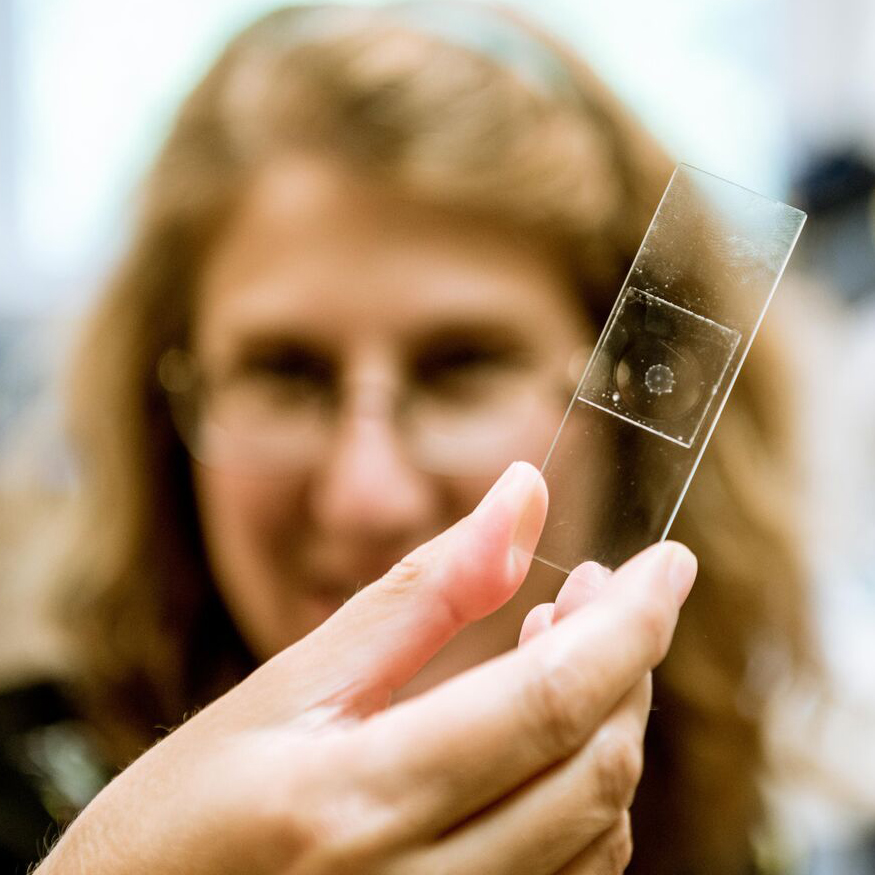

Jocelyn Malamy, Associate Professor of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology at UChicago, studies regeneration and wound healing in the C. hemispherica jellyfish.

Jocelyn Malamy, Associate Professor of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology at UChicago, studies regeneration and wound healing in the C. hemispherica jellyfish.At this point, Malamy has no shortage of research pursuits. She devised the jelly donut technique last summer, removing the manubrium core in order to watch it regenerate. In doing so, she realized there were two separate processes at play: the regeneration itself came after wound healing, when the epithelial tissues re-sealed.

Malamy first analyzed the former operation, asking where and how cells were made to re-create the new manubrium. To her surprise Malamy found that—at least during the early stages of regeneration—the majority of these cells were not made by a burst of new cell divisions on the spot. Rather, they were pre-existing cells that had migrated to the site of injury from other areas. The precise source of these cells still remains unclear.

This summer, with the help of high school teacher Harry Kyriazes and UChicago undergraduates Katie Zellner and Zach Kamran, Malamy has shifted her focus to the initial step of regeneration: wound healing. “Regeneration is always triggered by something being taken away or bitten off,” she says. “So wound healing is key to questions of regeneration; the two are intimately connected.”

Malamy analyzes a jellyfish specimen in the Whitman Center.

Malamy analyzes a jellyfish specimen in the Whitman Center.Jellyfish are particularly well suited to wound healing experiments because the repair process in the epithelium is easy to image—the big, flat epithelial cells exist in a single layer, and sit on top of transparent jelly. Most organisms are far too complex to visualize wound healing directly in the animal, and thus researchers are often forced to examine cells in artificial culture systems.

By contrast, jellyfish permit imaging in vivo—Malamy can scratch the surface epithelial cells and watch the wound heal in the organism rather than in a dish. Using a standard light microscope, Malamy can see the cells come together in sheets, extend feelers to locate one another, and simultaneously contract in draw-string fashion to pull the wound closed. A novel microscope designed by MBL Associate Scientist Michael Shribak has provided her with an even greater level of resolution.

“We’re not used to having this kind of resolution in live systems,” Malamy says. “Our imaging is so powerful that we may find processes that occur differently in the animal versus in the culture dish, which could lead to a reexamination of previous findings.”

Malamy is working to identify specific molecules involved in injury re-sealing. That said, her wound healing experiments have literally just scratched the surface of what this organism has to offer.