Lights, Camera, Action! MBL Creates Library of High-Definition Video of Research Organisms

The octopus scuttled away from the bright lights to a dark corner of the tank and swiftly pulled a rock in front of its sinuous body.

“It knows where the camera is – we don’t know how – and builds a house in the opposite corner,” noted Daniel Stoupin of BioQuest Productions, a film studio that specializes in underwater cinematography for projects such as the BBC’s “Blue Planet” series.

BioQuest was in the midst of a 4-week stay at the MBL in June and July, during which they collaborated with MBL scientists, course faculty and students to shoot high-quality videos of organisms important to MBL education and research, past and present.

“This octopus is, by far, the most difficult subject we’ve had to date. Its nature is to avoid bright lights, but we need those lights to get images in the camera,” said Pete West of BioQuest. “You get used to it! It can sometimes take weeks for animals to get accustomed to filming conditions.”

“I’m always interested in finding new ways to promote the diversity of organisms that we work on at MBL, especially as we work to increase their experimental usefulness through advances in husbandry, imaging and genetic tractability,” Patel said. “And it’s always fantastic to see high-quality footage.”

Once edited, videos will be available to scientists for their presentations as well as for a variety of MBL outreach activities. Patel is also exploring the possibility of making the footage commercially available to film studios, broadcast news outlets, and other media companies that are more than eager to obtain high-definition clips of marine organisms.

While some of the footage was acquired on microscopes, “BioQuest has high-end equipment for macro photography, so we mainly focused on whole organisms and close-ups,” Patel said.

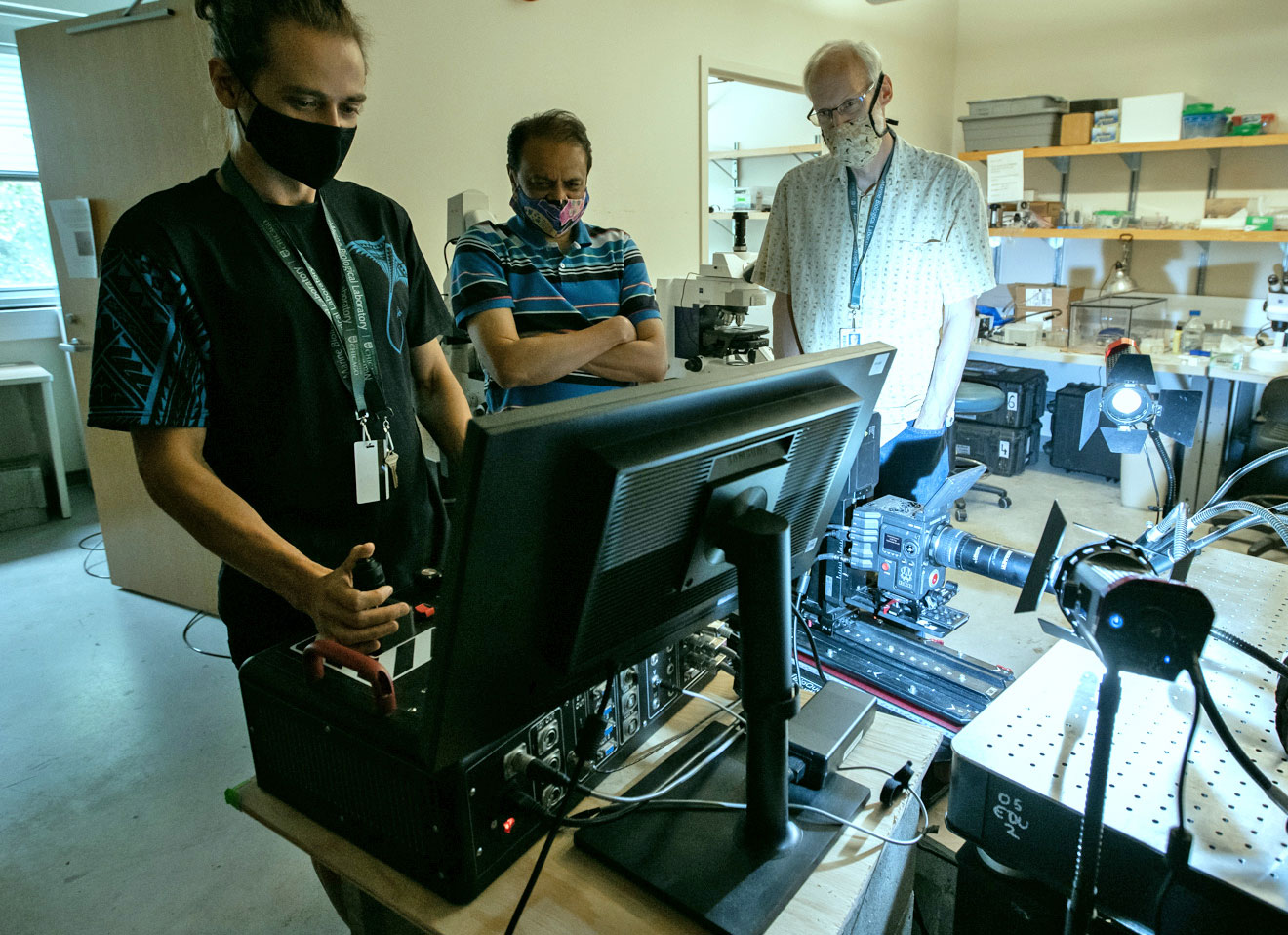

From left, Daniel Stoupin of BioQuest, Nipam Patel and Jon Henry of MBL filming marine organism videography at MBL this summer. Credit: Pete West

From left, Daniel Stoupin of BioQuest, Nipam Patel and Jon Henry of MBL filming marine organism videography at MBL this summer. Credit: Pete WestEarly video shorts culled from nearly 40 terabytes of footage show spectacular results. A purple-and-red nudibranch is so electrically vivid, it looks fluorescently enhanced, but Patel said all the organisms were filmed in natural color, including these beautiful species.

In another video, a male amphipod crustacean (Parhyale hawaiensis) holds onto a female, guarding her from other males until she molts and he can fertilize her eggs.

“Some of the footage revealed how a male goes about securing the female with his specialized claws, which is something we had never observed before,” said Patel, whose lab spent years establishing Parhyale as a tractable organism for evolutionary-developmental research.

The collaboration pulled in a wide swath of MBL scientists and staff. “We could not have done this without MBL’s facilities and equipment,” said West, including “out-of-this-world” microscopes and the expertise of Louis Kerr, director of Imaging Services.

Daniel Stoupin of BioQuest adjusts a small tank with cherry shrimp in preparation for videotaping at MBL. Credit: Alison Crawford

Daniel Stoupin of BioQuest adjusts a small tank with cherry shrimp in preparation for videotaping at MBL. Credit: Alison Crawford“We had [Senior Aquarist] Jon Henry building little tanks for the organisms, and Jon and I were in there every day collecting embryos or prepping animals in the miniature tanks,” Patel said. “Everyone from the Marine Resources Center was super helpful in collecting some of the animals and bringing them back and forth to Loeb Laboratory for filming. In addition, we were able to tap into the resources and knowledge from some of the summer courses.”

The group had a priority list of organisms to film, but fresh ideas arose as they went along. “On the last day, [Director of Marine Research Services] Dave Remsen suddenly said, ‘There are these flatworms that live inside of hermit crabs. You should film them.’ He pulled one out of a crab and it was just fantastic,” Patel said. “Someone from the Physiology course suggested Stentor, so we spent a few hours filming them. Mark Terasaki, a Whitman scientist, helped film scallops running away from sea stars. It was great.”

BioQuest’s expertise in cinematography intersected well with MBL’s strengths in organism collection and care. For example, “During one filming they had a light slowly blinking on and off, and I thought, ‘Why are they doing that?’” Patel said. “If you are actually underwater, as waves go by, the light gets brighter and dimmer. So this blinking made the video look really natural.”

The successful collaboration may expand in the future to establish a small “film studio” at MBL, to support other filming projects and which MBL scientists could learn to use.

“Looking at an organism under a microscope, which scientists usually do, is one thing. But seeing it move around in a somewhat more natural setting, especially with close-ups that we can do – We’ve had many surprises,” West said.

The humble flatworm Planeria took the most unexpected star turn. After Patel pipetted it down onto some rocks, it glid gracefully around on its cilia, lifting its head to look around, and then took a swan dive off the edge of a rock.

“All the scientists associated with Planaria couldn’t believe it!” West said.

“You just don’t get an appreciation for this kind of behavior when you are looking at it from above, through a microscope,” concurred Patel. “Things you wouldn’t think look interesting look pretty amazing from this angle.”

Featured Image: Screenshot of the Spanish shawl nudibranch (Flabellinopsis iodinea; courtesy of Deirdre Lyons) from MBL-BioQuest footage. Nudibranchs are soft-bodied marine gastropod molluscs known for their extraordinary colors and forms.