Transient Droplets Organize Biochemical Reactions Inside Cells | C&E News

MBL Whitman scientists spanning centuries -- from E.B. Wilson in the 1890s to Clifford Brangwynne, Anthony Hyman, Michael Rosen, Amy Gladfelter and others today -- are part of the discovery story of phase separation in cells and how it may relate to a host of diseases.

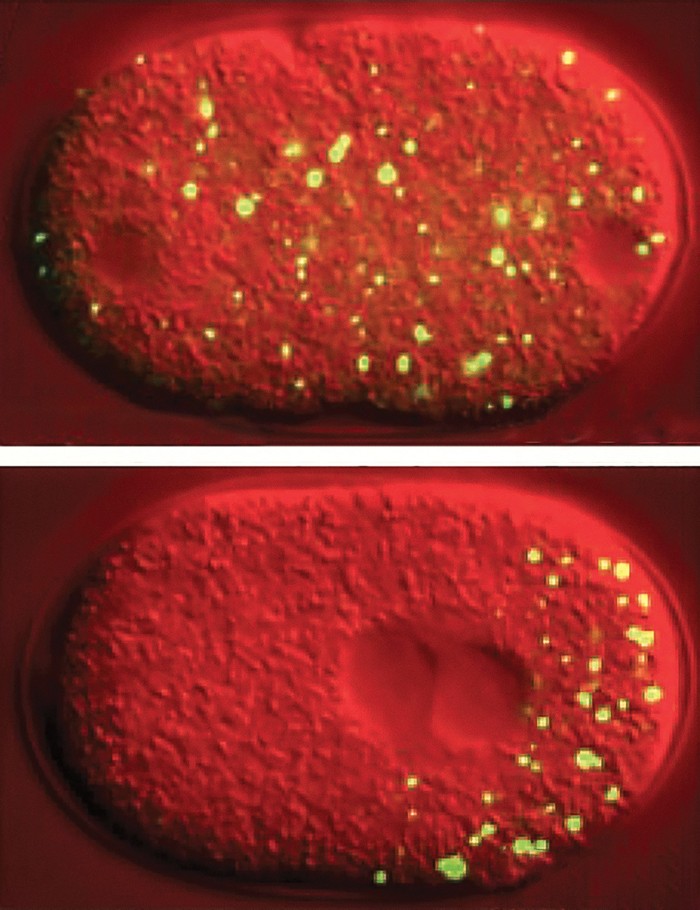

In the single-celled embryo of the roundworm C. elegans (top), clumps of RNA and protein known as P granules cluster on one side of the cell (bottom) to direct the worm's development. This observation, first made in the MBL Physiology course, was reported In a seminal 2009 Science paper by Brangwynne et al showing that P granules form by liquid-liquid phase separation. Credit: Science

In the single-celled embryo of the roundworm C. elegans (top), clumps of RNA and protein known as P granules cluster on one side of the cell (bottom) to direct the worm's development. This observation, first made in the MBL Physiology course, was reported In a seminal 2009 Science paper by Brangwynne et al showing that P granules form by liquid-liquid phase separation. Credit: ScienceClifford P. Brangwynne smashed the single-celled embryo between a microscope slide and a thin glass cover slip. Then he peered into the microscope to get a look at the cell, taken from a worm commonly studied in the lab, Caenorhabditis elegans. What he expected to see were small, solid balls, composed of RNA and protein, dotting the cell. But instead, what he saw looked more like the world’s smallest lava lamp.

Rather than drifting throughout the cell’s liquid innards like wooden balls bobbing around in a tank of water, over and over the globs appeared, merged, and separated before disappearing. Brangwynne, then a postdoctoral scholar in Anthony Hyman’s lab at Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG), realized: this isn’t something that solids do. The so-called P granules, which scientists had assumed were solids, were actually behaving like liquids.

“All of a sudden, everything made sense,” Brangwynne says. Scientists had been trying to understand how cells organize the biochemical reactions going on inside, keeping them separate so they didn’t interfere. The tiny lava lamp he watched undulating under the microscope held an answer.

What Brangwynne had observed through the microscope was a phenomenon called liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS). In LLPS, an otherwise heterogeneous, well-mixed liquid can separate into two distinct phases, just as a vinaigrette salad dressing will naturally separate into an oil layer and a vinegar layer in the bottle. Read more of the article here.

Source: Transient droplets organize biochemical reactions inside cells | C&E News