MBL Scientists Celebrate Adaptations this Darwin Day

February 12, the anniversary of Charles Darwin’s birthday is affectionately known as “Darwin Day” in the scientific community. This year, in honor of the famed biologist’s birth, MBL scientists highlight their favorite adaptations in the animal kingdoms.

An octopus exhibiting dynamic camouflage. Credit: Roger Hanlon

An octopus exhibiting dynamic camouflage. Credit: Roger HanlonDynamic Camouflage by Cephalopods

“Within the realm of natural selection, one of the commonest adaptations is camouflage, which is a primary defense against predation and is shown by nearly all taxa. However, most animals have a single static camouflage pattern that limits its use to one or a few habitats.

By contrast, cephalopods have evolved dynamic camouflage, which is an extreme adaptation because it enables these soft-bodied molluscs to move around and settle within any environment and camouflage instantly (<1 second). The speed and diversity of dynamic camouflage in cephalopods is unparalleled in nature. Octopuses, cuttlefish, and squid all exhibit it.”

Roger Hanlon, MBL Senior Scientist

American lobster (Hamarus americanus). Credit: Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons License

American lobster (Hamarus americanus). Credit: Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons LicenseJointed Legs of Arthropods

“My favorite adaptation is the jointed legs of arthropods (lobsters, crickets, spiders, centipedes, etc). Arthropods have many pairs of legs, and their legs are super modular. So they can modify different pairs of legs for different tasks and situations. '

A lobster has pairs of legs for smelling (antenna), for chewing (mandibles), for cleaning their mouth and their food (maxillae), for holding their food (maxillipeds), for pinching and snapping (claws), for walking, for swimming (swimmerets), and for making a quick getaway (uropods on tail fan).

So many different tools you can make by starting from a simple leg blueprint!”

- Heather Bruce, MBL Research Associate

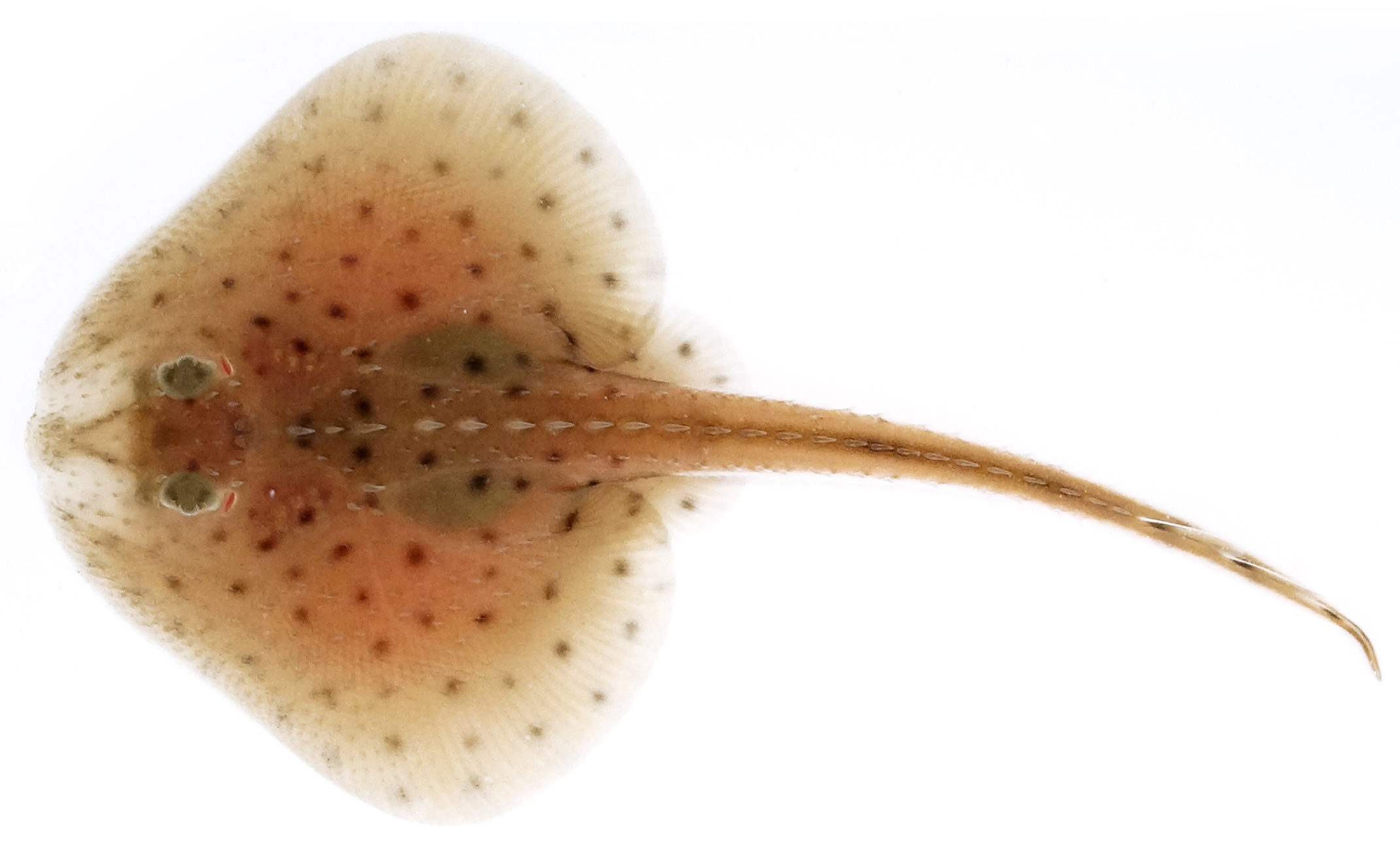

Little skate (Leucoraja erinacea). Credit: J. Andrew Gillis

Little skate (Leucoraja erinacea). Credit: J. Andrew GillisSpiracles in Cartilaginous Fishes

“I would say that my favorite adaptation is the spiracle—a small opening into the oral cavity that is located behind the eye of many cartilaginous fishes (sharks, skates and rays). It’s particularly prominent in my favorite animal, the little skate (Leucoraja erinacea).

Most fishes breathe by sucking water in through their mouth, and pumping it out over their gills - but this doesn’t work very well when you spend your life on the seafloor with your mouth in the muck... Skates and rays use their spiracle like a little snorkel— not for air, but for clean, oxygenated water—when their mouth is not up to the task!”

- Andrew Gillis, Incoming MBL Scientist

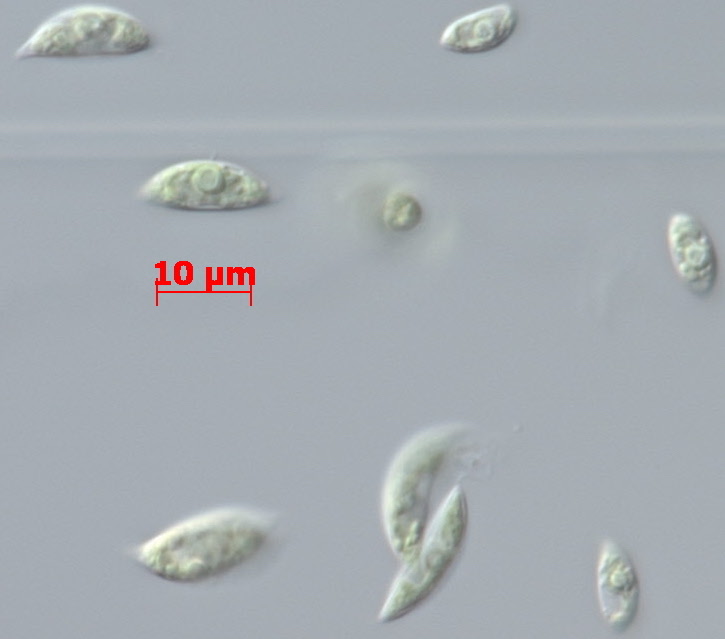

Tetradesmus deserticola SNI-2 in liquid culture. Credit: Elena L. Peredo

Tetradesmus deserticola SNI-2 in liquid culture. Credit: Elena L. PeredoDesiccation Tolerance in Green Algae

“My favorite adaptation is the remarkable desiccation tolerance found among microscopic, single-celled, green algae that inhabit microbiotic crusts in deserts. They do not live in a puddle! They live right in the dry soil crust.

One alga in particular, Tetradesmus deserticola, is a beautiful representative. It is shaped like a lemon, it can be dried down to dust and then rehydrated with a raindrop, and voila! It starts photosynthesizing again, within seconds. It's also fairly closely related to Tetradesmus obliquus, an aquatic green alga that is of great interest to biofuels and bioproducts industries, so there are interesting industrial possibilities for this incredibly stress tolerant, desert-dwelling relative.”

- Zoe Cardon, MBL Senior Scientist