Nature or Nurture: How Does an Animal Get its Microbiome?

We know that sharks are voracious eaters, but what do we know about the source of its microbiome? To date, not much. But a recent study from the University of Chicago and the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) fills a gap in understanding the microbiome associated with a close relative in the Chondrichthyes, a class of fish that includes sharks, rays and skates.

Postdoctoral Scholar Katelyn Mika and Alexander Okamoto, then an undergraduate at UChicago, were inspired to discover how the microbiome originates in the little skate in 2018, while spending the summer at MBL with UChicago Professor Neil Shubin. Also guiding them in the research was MBL Senior Scientist David Mark Welch.

“There’s a new understanding that microbiomes are very important for all multicellular organisms,” said Mark Welch, senior author on the paper. “We're essentially taking what we’ve learned from the NIH Human Microbiome Project, including the central role the microbiome plays in human health, and recognizing that microbiomes play a role in a wide variety of organisms, particularly marine organisms.”

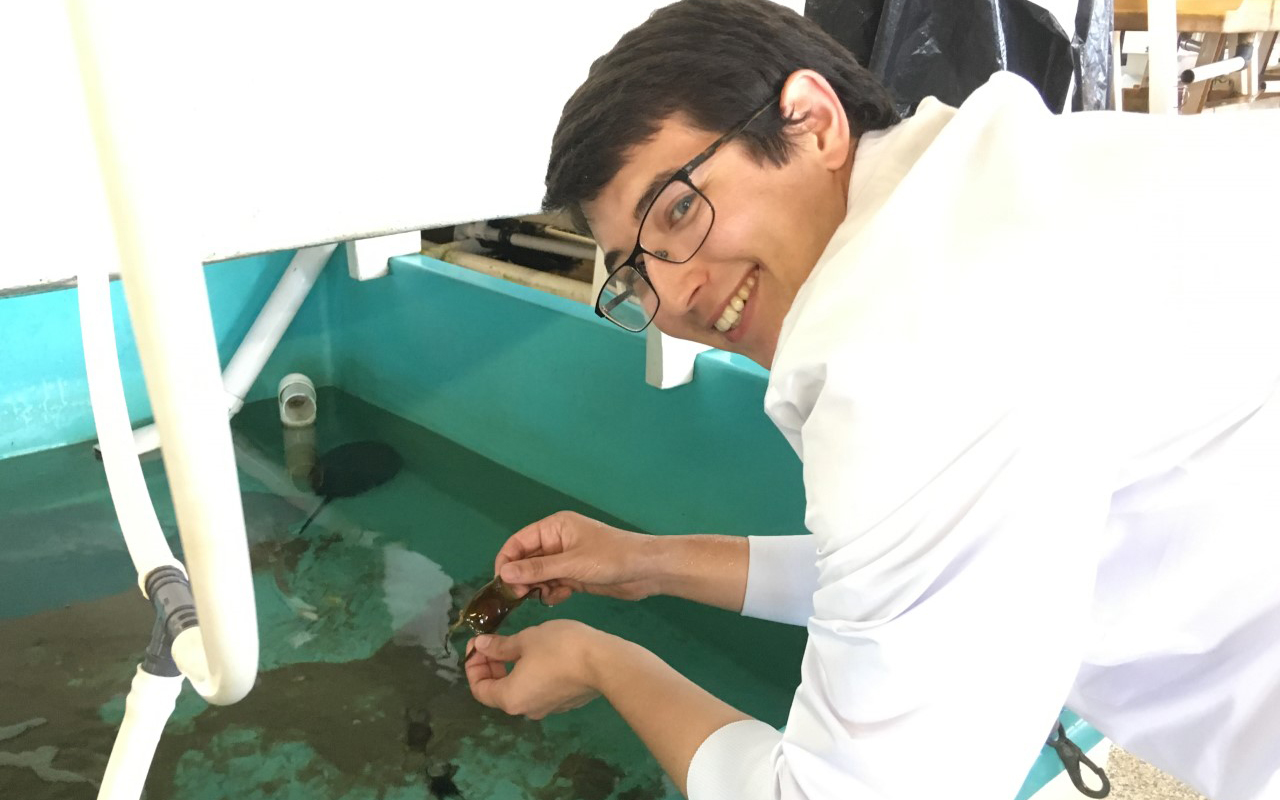

Alexander Okamoto holds a skate egg case (Leucoraja erinacea) in the MBL Marine Resources Center. Credit: Marine Biological Laboratory

Alexander Okamoto holds a skate egg case (Leucoraja erinacea) in the MBL Marine Resources Center. Credit: Marine Biological LaboratoryAmong the ocean dwellers, corals and certain fish have had their microbiomes analyzed, but “there are huge gaps [in knowledge], and one of them has been the microbiomes of non-bony fish – sharks, rays, skates and other cartilaginous fish,” Mark Welch said.

An animal can acquire its microbiome in three different ways, the team’s study explains. First, the parent can transmit all or part of its microbiome to its offspring. Second, the animal can acquire it during social or sexual interactions with other members of its species. And third, animals can recruit microbes from their environment through contact with fluids, habitat, or diet. Humans acquire their microbiome in all three ways.

The little skate’s embryo develops in the contained environment of an egg case, commonly called a devil’s purse.

An adult little skate (Leucoraja erinacea) in the MBL Marine Resources Center. Credit: Andres Pruna

An adult little skate (Leucoraja erinacea) in the MBL Marine Resources Center. Credit: Andres Pruna“The skate egg case is a very interesting place to study microbiome development because the egg is separate from the outside world up until a certain stage of development, when little apertures open in the egg case and there starts to be an exchange with seawater,” said Mark Welch. “So, you can ask the question more easily than in other organisms, is there vertical transmission of the microbiome? Namely, does the mother pass on part of her microbiome to the offspring?”

Mika and Okamoto got on the trail of this question when they heard a talk by Andrew Gillis, who is joining the MBL next year as an associate scientist. Gillis’s description of the skate egg case opening to the environment about two-thirds of the way through development caught their attention.

“We began wondering what happens with the microbiome, given the egg’s fairly dramatic life history changes,” said Okamoto. “It’s basically dumped on the bottom of the ocean, abandoned by its parent for many months, and then it opens up suddenly and seawater rushes in.”

“Alexander and I looked at each other and said, ‘That's weird,’ because most eggs are fully sealed until the time of hatching, and these are not,” said Mika.

They conducted the research during the summer of 2019, while Okamoto was working as a research assistant in MBL Director Nipam Patel’s lab. Using next-generation sequencing to characterize the microbial community at six points in the skate’s embryonic development, their efforts yielded the first evidence of vertical transmission of the microbiome from parent to offspring in the Chondrichthyes.

Katelyn Mika and Alexander Okamoto by the Rachel Carson statue in MBL’s Waterfront Park. Credit: Alexander Okamoto

Katelyn Mika and Alexander Okamoto by the Rachel Carson statue in MBL’s Waterfront Park. Credit: Alexander Okamoto“This was the first microbiome study Alexander and I had ever done,” said Mika. “I'm a geneticist and he's worked on evolutionary and organismal biology, so we were both a bit out of our depth. We had to learn as we went.”

Their findings are a useful step in the study of microbiomes, which can be indicators of how well an organism is doing in its environment, said Mark Welch.

“We know that a lot of marine species are under stress because of anthropogenic changes, global warming,” he said. “One of our broader goals is to be able to study the microbiomes of these organisms and determine very quickly, how healthy are they?”

There’s plenty of room for more research on animal microbiomes, said Mika – including on sharks.

“There's a chain catshark at the MBL whose eggs look incredibly similar to the skates' eggs,” she said. “They go through the same sort of development where they're in that egg case for the first two thirds, then they have slits that open, and then they finish developing with that open waterflow through the eggs. I'm desperate to know if their microbiomes are similar to the skates' or if they're totally different.” Sounds like a good reason to come back to the MBL!

This research was funded by a grant from the Microbiome Center, a collaboration between University of Chicago, Marine Biological Laboratory, and Argonne National Laboratory; and by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship to Alexander Okamoto.

Citation:

Katelyn Mika, Alexander Okamoto, Neil Shubin and David Mark Welch (2021) Bacterial community dynamics during embryonic development of the little skate (Leucoraja erinacea). Animal Microbiome, DOI: 10.1186/s42523-021-00136-x

—###—

The Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) is dedicated to scientific discovery – exploring fundamental biology, understanding marine biodiversity and the environment, and informing the human condition through research and education. Founded in Woods Hole, Massachusetts in 1888, the MBL is a private, nonprofit institution and an affiliate of the University of Chicago.