Thinking Big: MBL Historian Reflects on Science, Policy, and Digitization

The MBL is home to a variety of researchers studying a myriad of life forms, but Jane Maienschein is an expert on one particular, understudied species—a sub-classification of historian known as the "historian of science." She also happens to be one herself.

MBL Fellow Jane Maienschein of Arizona State University.

MBL Fellow Jane Maienschein of Arizona State University.Maienschein has co-directed the annual Seminar in the History of Biology at the MBL since 1987, and in 2013 she launched the digital MBL History Project, amassing and recording the Laboratory’s rich past. Named an MBL Fellow this year, Maienschein is University Professor, Regents’ Professor, and President’s Professor at Arizona State University, where she directs the Center for Biology and Society.

“We look to history to gain perspective,” Maienschein says. “That is, to understand why we do certain things, make certain choices, study certain organisms, and ask certain questions.”

In a recent article published in the journal ISIS, Maienschein explains that perspective and “long-term thinking” are synonymous—and undervalued. As part of an initiative to highlight the role of open-access publishing in making scholarly literature widely available, ISIS had asked Maienschein and others to review a recent open access book: The History Manifesto.

“Open access invites international conversation, and The History Manifesto urges us to think big,” Maienschein says. “As historians and scientists, we tend to get hung up on the details of our small-scale studies, so it’s a way of reminding us to look at the bigger picture.”

The need for perspective is one of the book’s three main themes and feeds directly into the second one. If scientists and historians alike could master the art of “longue durée,” as historians call it, their research would be more likely to inform policy-making.

While working as a science advisor on Capitol Hill, Maienschein noticed that congressmen often resisted research if individuals failed to present their work in a larger context. Scientists’ favorite models for global warming were easily dismissed if they did not present them in the context of decades of research. Gene and stem cell manipulation can also appear far more alarming when divorced from the preceding science.

“In my experience working with congressmen and federal judges,” Maienschein explains, “if you can clarify the ‘so what’—what you’re doing and why it’s important—then you can spark a really good conversation, even with skeptics.” Once again, it all comes back to articulating the larger perspective, and acknowledging that history could unite the research and policy-making spheres. But first, science and history must also integrate.

The Manifesto’s third theme, digitization, is all about connecting the work of scientists and historians across time and space using data “repositories.” In other words, using technological tools to link corresponding research, creating a cohesive story to manage public issues (e.g., rising water).

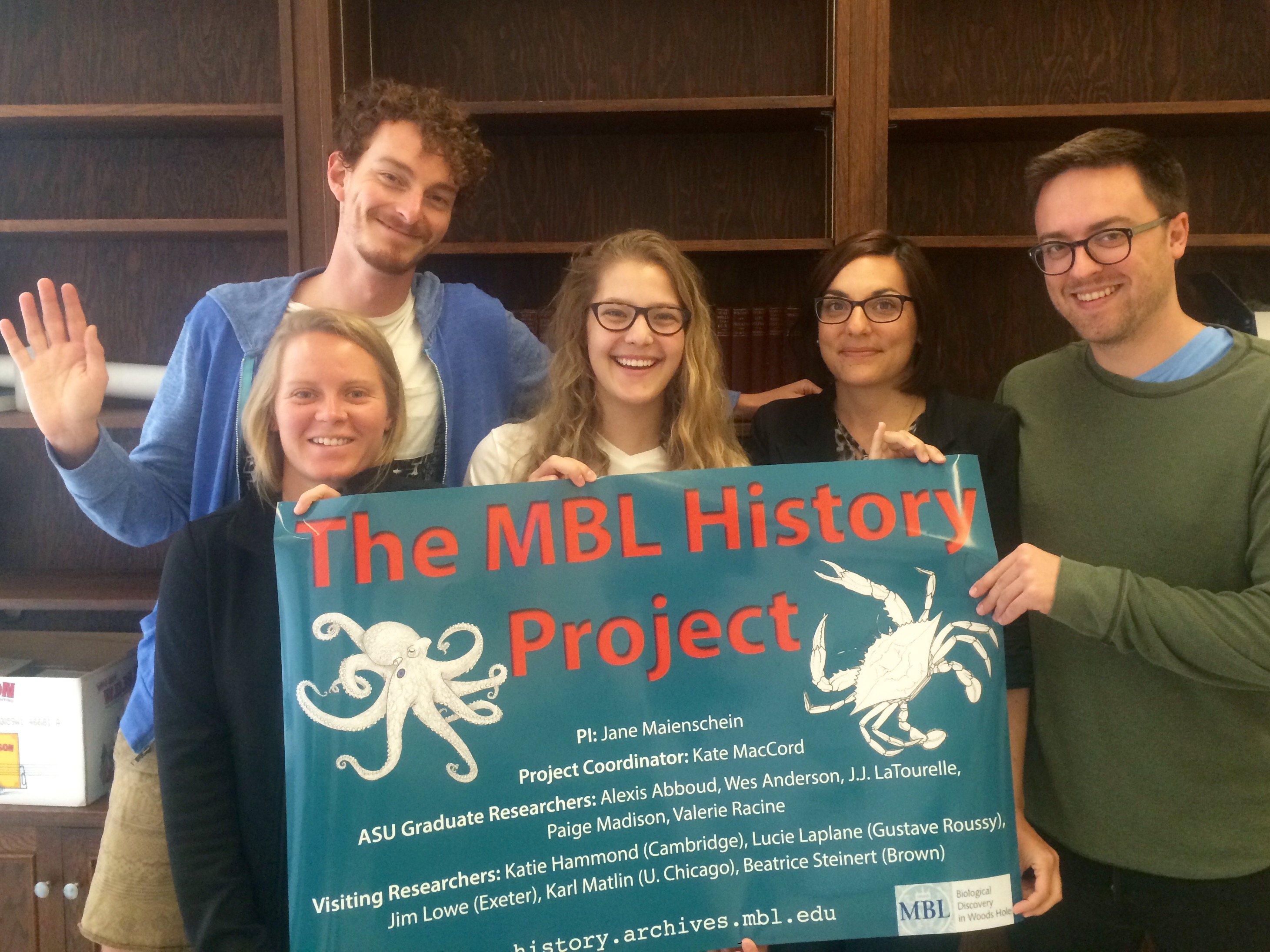

Arizona State University students and members of the MBL History Project team. From left to right: Jonathan (JJ) Latourelle, Paige Madison, Alexis Abboud, Valerie Racine, and Wesley Anderson.

Arizona State University students and members of the MBL History Project team. From left to right: Jonathan (JJ) Latourelle, Paige Madison, Alexis Abboud, Valerie Racine, and Wesley Anderson.“Digital archives allow us to see more than just what’s in front of us,” affirms Maienschein. “That’s why we started the MBL History Project—to connect stories of people, places, practices, and ideas, and make them more accessible.”

The MBL is characterized by diverse individuals with diverse interests, many of whom are here at different times of the year. The History Project helps to maintain a year-round sense of togetherness, offering manuscripts, photographs, and videos that capture the life, community, and science (which, in many cases, are one in the same). Three exhibits are currently on display in the Lillie Library lobby and the Bay Reading Room.

“The MBL is not just a bunch of scientists having fun at the seashore; we’re coming together and doing better science, more science, and science with students,” says Maienschein. “Digitization at the MBL and elsewhere shows the results and thereby helps spread ideas and knowledge that can be used by policymakers to inform wise decisions.”

Given this explanation, it seems the historian of science is one species the MBL ecosystem—and the global community, for that matter—can’t do without.